Article originally published in the January 1998 edition of The West Side, the official YCHS newsletter. Written by historian and West Side editor John White (1928-1999).

Yamhill Coal Mine

At the close of the last century John Goeser and his wife Amy were working their 160 acre farm about 3 1/2 miles northeast of Yamhill on Laughlin Road. In May 1898, their son William was engaged in the task of cleaning out a hillside spring on the place when he made a remarkable discovery. Under the scrub growth surrounding the spring appeared an outcropping of lignite coal. Digging about a bit further Will noted the deposit seemed to gain in size as it drifted further down and deeper into the hillside.

Over the course of the next several months Will followed the slender vein by excavating a tunnel into the hill using only pick and shovel for tools. At first the work was not too difficult, but as the tunnel grew longer, removal of excavated earth became more difficult and provisions to prevent cave-ins required increasing effort which slowed the overall project considerably. By the time Goeser’s hand-dug tunnel had penetrated a distance of about 80 feet, another serious problem arose. Large volumes of water from the spring that had been responsible for the original coal discovery were now flowing unchecked into the hole. Clearly, if operations were to continue and a profitable mine eventually developed, more sophisticated equipment and expertise would be required.

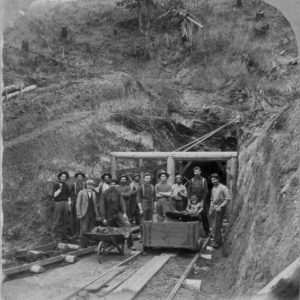

The Goeser family negotiated an arrangement with the Portland Coal and Development Company early in 1901 and by July of that year professional mining operations were begun on the site. A provision of the agreement stipulated that Will Goeser was to be hired by PC&DCo as “Foreman of Construction”, but it would be William Stedman and later a Captain Spiery, both veteran mining superintendents, who would actually direct and oversee all aspects of the operation. Except for one or two experienced miners acting as lead men, the balance of the twelve man crew were laborers hired locally for a wage of $1.50 per ten hour work day.

A diversion channel soon removed the water problem, a nearby stand of fir trees provided a stockpile of timbers that would be required for shoring within the mine and finally, steel rails to accommodate a mule-drawn cart shuttling in and out of the mine were laid. Although the quality of coal so far recovered was marginal and in rather small quantity, Mr. Stedman noted several geological factors which led him to believe a major deposit of marketable fuel could possibly be located much deeper into the hillside and his crew began drilling generally following the direction taken by the exposed vein.

By June of 1902, at a cost of $9000.00, excavations had been extended about 1000 feet underground with more than 1300 feet of track laid for the mule cart. (The greater length of track was required to ensure tailings and rubble from the mine would be dumped well away from the Goeser’s orchard – a provident plan as it later turned out). A second tunnel branched off from the original about 200 feet from the entrance tracing another vein also thought to eventually lead into the expected major deposit. With two points of access, Mr Stedman reasoned when the principal concentration was located, coal extraction could be expedited considerably and therefore be more profitable

As work progressed samples being taken were changing from a softer consistency having a brownish black color to harder and shiny black specimens of much higher quality. In the opinion of a few experts, the grade of some samples approached that of coal then being found in Australia and Japan – some of the finest in the world! These encouraging prospects also enticed the Southern Pacific Railroad to investigate the possibility of establishing a spur line from the vicinity of Cove Orchard on its main West Side line over to the mine site. Certain that a major deposit of high grade fuel now lay close at hand, PC&DCo management increased the labor force to eighteen men and reduced the work day to nine hours as an added incentive.

As the weeks rolled by however it became increasingly apparent that those premium samples had been extracted from a few isolated small pockets. Once past these points the vein began opening up as expected, but the quality was well below any profitable level. Work continued at an increased wage of $1.75 per nine hour day, but with a crew reduced to six or eight men. Finally in 1903 operations ceased entirely and the mine was permanently closed.

The story does not end here. Sometime during 1902 a drill had become firmly stuck in hard rock and when finally extracted it was discovered its six diamond bit tips had been broken off and remained solidly embedded in the stone. Not long after the mine closed a rumor circulated, aided by some encouragement from the North Yamhill Record newspaper, that “six diamonds as big as hazelnuts” still lay abandoned down in the hole. Numerous recovery schemes were devised but those thinking of salvaging what they believed might be a fortune in six precious stones were disappointed to learn drill tips consist of a cluster of quite small industrial grade diamonds, not a single large gem. Also, to further discourage amateur treasure hunters from trespassing on Goeser’s property, PC&DCo released the information that the original purchase price had been less than $100.00 per tip.

Sometime during 1904 the pile of rubble containing many tons of low grade coal tailings hauled from the mine became ignited, probably by spontaneous combustion. Since fires of this type are extremely difficult to extinguish and in this case no serious threat was posed to surroundings, the fire was allowed to smolder itself out – a process eventually requiring almost two years! When finally cooled the residual ash and slag resembled finely crushed rock in character and was of an extremely bright orange-red color. This material was discovered to be excellent for surfacing unpaved roads so the saga of Will Goeser’s coal mine was extended for a bit longer through several scarlet hued byways in the vicinity of North Yamhill and the upper Chehalem Valley.

Help us gather, preserve, and share Yamhill County History. Become a member or donate. Thank you for your support!